Facing fuel shortages, California seeks a buyer for a retiring refinery to increase production

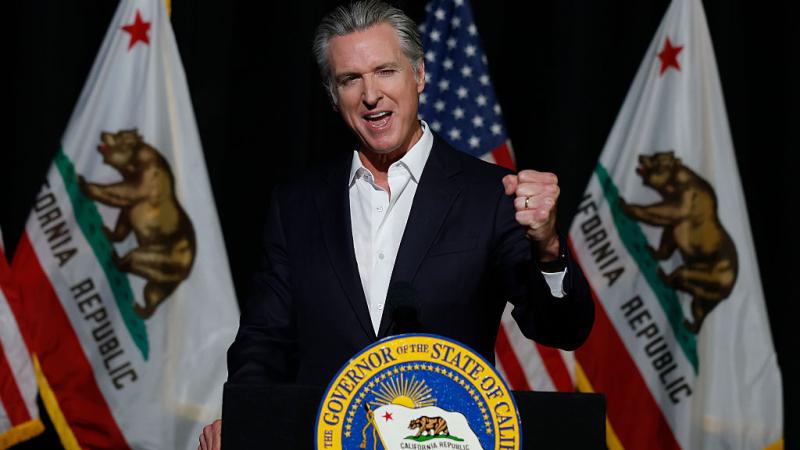

With a second refinery closing and possibly more to follow, Newsom may be forced to consider the possibility that petroleum might not be as dispensable or easily replaceable as he thought.

California set out to be the nation’s leader in the energy transition, but it isn’t going quite as planned.

In October, Phillips 66 announced it was closing down its Los Angeles-area refinery, which analysts say was the result of the state’s hostility toward its oil industry. Then in April, Valero announced it would cease operations at its San Francisco-area refinery in April 2026.

Facing serious shortfalls of gasoline, jet fuel and diesel, the state is now hoping to broker a deal for a buyer to take over the Valero refinery, Reuters reported, so that it may keep the facility running. The California Energy Commission (CEC) wouldn’t confirm its engaging buyers directly, but it did confirm to Reuters that it’s trying to keep the facility open.

University of Southern California professor Michael Mische told Just the News that California Gov. Gavin Newsom, a Democrat, and the state’s legislature weren’t quite prepared for one refinery shutting down. With a second refinery closing and possibly more to follow, the state may be starting to consider the possibility that petroleum might not be as dispensable as they thought. The state's Assembly has been in Democratic hands since 1970, and the Senate has been under Democratic control since 1975.

“Two refineries shutting down? That gets everybody's attention, but if you have a third that is, that is something that's very, very difficult to deal with,” Mische said.

Impact extends past California's borders

While the state’s energy policies hit its drivers with some of the highest gasoline prices in the country, the impacts spread well beyond the state’s borders. California is home to 41 military bases. In 2019, California consumed nearly 17% of the nation’s jet fuel, and its nine international airports serve travelers all across the U.S. According to Mische, California also supplies Nevada with 88% of its gasoline and nearly half of Arizona’s, and it also supplies those states’ military bases with their transportation fuels.

Following Valero’s announcement, Newsom asked the CEC to provide recommendations on how the state could ensure California has a supply of transportation fuels. Siva Gunda, vice chair of the CEC, replied in June with a series of recommendations that suggest maybe the state should step up its oil production.

While Gunda reaffirms the state’s goal of eliminating fossil fuel use, which he says is “critical to protecting our communities’ health,” he also argues that the state might want to increase its production of crude oil. Increasing its production of oil would be, he explained, part of its energy transition.

“As part of a managed transition strategy, we recommend that the state take action to achieve targeted stabilization of crude oil production in California to supply in-state refineries while ensuring that production is consistent with critical health and environmental protections,” Gunda wrote.

California has no inbound pipelines by which it could import transportation fuels from other U.S. refineries. Mische and Ronald Stein, an engineer and energy consultant, explain in the “Energy Security and Freedom” Substack, that the state’s environmental policies require special blends of gasoline, so its refineries cannot ramp up production with generic refining methods. They are required to produce complex, seasonal and cleaner-burning fuel blends, which need dedicated infrastructure and have limited flexibility.

Gunda said the shortfall in refined products would be made up by increased imports of these special blends from overseas, and more storage for its imported transportation fuels would be needed for those increased imports. Gunda also says that given sufficient time, the petroleum market is likely to find a new equilibrium following the disruption of a refinery closure.

But at what price?

“It doesn't take a brain to know that the market will supply the product. The question is, at what price will the product be supplied to the California consumer?” Mische points out.

Mische said that importing gasoline to California consumers would come with a price of about $0.30 more per gallon under the most ideal conditions. The shipping costs alone are $0.17 per gallon, depending on the type of ship and where it comes from. However, any number of events disrupting imports could raise that cost, including hurricanes, geopolitical situations or labor disputes at the docks.

“Let's face it. It's going to be fragile, because this gasoline is going to be coming in from all over the place,” Mische said.

On top of that, some of these products may come from Russia, Iran or Venezuela, meaning California consumers will be, as a result of the state’s policies, supporting nations hostile to America.

While the imports may address shortfalls at a price, the state’s supply would remain dependent on its remaining refineries. After the Philips 66 and Valero refineries close, the state will be down to seven refineries producing gasoline compliant with California’s complex regulations. This means any disruption to any of them would spike gas prices in the state.

This could be a maintenance issue that could be quickly resolved, or something far worse. After the Valero refinery ceases operations, there will be two refineries operating in Northern California. One of those is the Chevron Richmond refinery, which sits right on the Hayward Fault. That fault, geologists believe, is due for a major seismic shift.

“If you had a catastrophic event, then you'd probably be looking at losing 50% of the gasoline in Northern California. So you'd have to import that gas through maritime vessels or tanker trucks, which would be an unlimited supply coming up the I-5 — or rail. Most likely, you’d have to put them on barges and bring them up the coast,” Mische said.

With the loss of 50% of the state’s gasoline production, Mische said, prices would go “through the roof.” This would devastate the state’s economy, and the impact would likely be felt throughout the country.

Chevron: "We are in a bit of a tipping point"

There’s also the possibility that another refinery could shut down. Andy Walz, president of downstream, midstream and chemicals at Chevron, told a Fox affiliate in Los Angeles that the state’s regulators may want to be more cooperative with the oil industry.

“We’ve been in California for over 140 years. We are proud of what we’ve done, but I think it’s becoming quite acute. We will have decisions we will have to make going forward, and I am urging regulations and state politicians to really think carefully about how they try to maintain reliable suppliers like Chevron. We are in a bit of a tipping point,” he warned.

California’s politicians may be listening to that message more closely than in the past. Politico reported last week that Newsom is proposing to ease permitting for new wells in existing fields that meet environmental standards.

California’s emissions account for less than 1% of the world's total. Even if the state were to decarbonize its entire economy — something it’s nowhere close to achieving — it wouldn’t have much impact on reducing greenhouse gases. Mische said the state is paying a lot for very little benefit.

“If it’s really such a minuscule amount, what are you really accomplishing by forcing these high prices on consumers?” Mische asked.

The Facts Inside Our Reporter's Notebook

Documents

Links

- Phillips 66 announced

- Valero announced it would cease operations

- Reuters reported

- Michael Mische

- highest gasoline prices

- home to 41 military bases

- Energy Security and Freedom

- seven refineries

- due for a major seismic shift

- Andy Walz

- told a Fox affiliate in Los Angeles

- Politico reported last week

- less than 1% of the global total