Trump-designated acting SEC chair Uyeda takes aim at criticized and contested climate rule

The rule would have required public companies to disclose corporate climate risks and targets and how they plan to manage those risks. An attorney for the PLF, said the rule effectively shamed companies for not pursuing climate goals.

The Security and Exchange Commission appears ready to quash the controversial climate disclosure rule, which will bring to an end the legal challenges dropped on it.

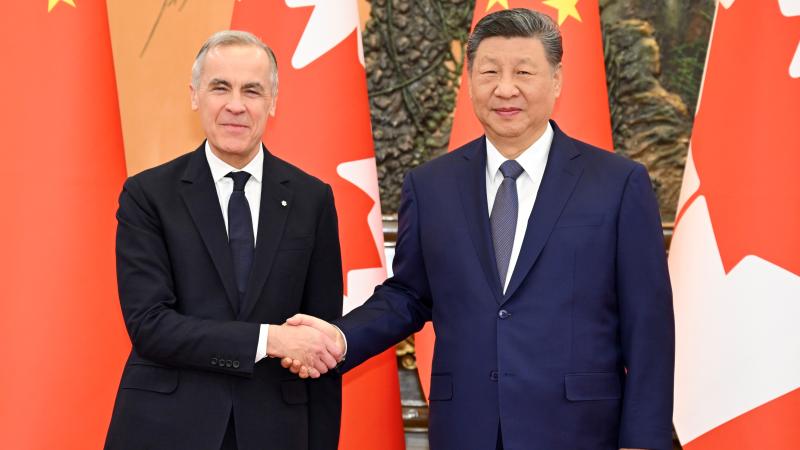

Acting Chairman Mark Uyeda, designated to the position by President Donald Trump, recently announced he’s taking action, arguing it’s “deeply flawed” and has the potential to “inflict significant harm.”

The rule, which was adopted in March, requires public companies to disclose corporate climate risks and targets and how they plan to manage those risks. This includes reporting the companies' Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions and how they plan to implement climate goals. Scope 1 emissions are those that come directly from a company’s operations, and Scope 2 emissions are those that come from their purchase of electricity, heating or cooling.

While the commission didn’t adopt the more stringent requirement of disclosing Scope 3 emissions, which would have required public companies to calculate and report emissions that occur throughout the entire supply chain of a product, critics say compliance with the rule is costly, the requirements are unnecessary, and the rule exceeds the commission’s authority.

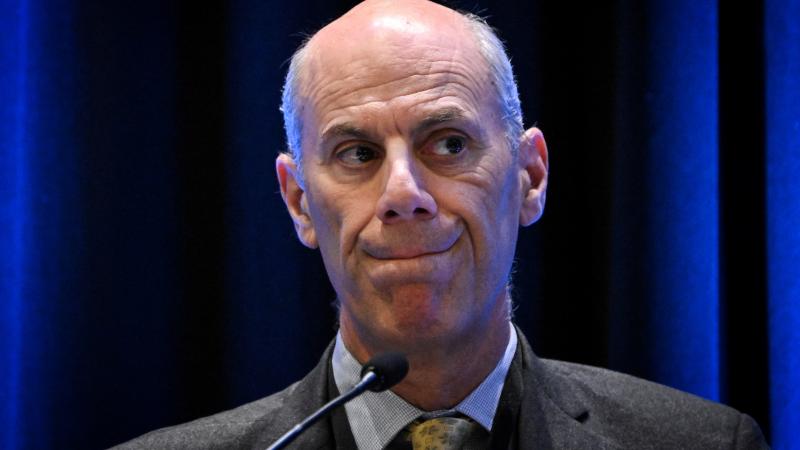

“The SEC was claiming a limitless power to require disclosures on anything and everything, just because some politically activist investors might say they want that information for social or political reasons, as opposed to purely financial calculus,” Luke Wake, attorney for the Pacific Legal Foundation (PLF), a public interest law firm, told Just the News.

‘Shaming’ companies

The rule faced a barrage of lawsuits from interest groups, trade associations and 43 states, The challenges were consolidated in the Eighth Circuit, and the SEC announced in April it would not implement the rule while the legal challenges played out.

The PLF is representing the Texas Alliance of Energy Producers and the Domestic Energy Producers Alliance in their suit seeking to block the rule.

Wake said that the disclosures the rule required would have effectively shamed companies for not pursuing climate goals. While the SEC couldn’t force companies to adopt such goals, Wake said the rule would have given the commission a means to pressure companies into it.

The rule would create an enormous administrative burden, critics also charge. Companies would need to report what systems they have in place to monitor and respond to all kinds of climate risks, including speculative concerns about regulatory changes or changes in consumer behavior. Critics also argue these risks would need to be disclosed even if they aren’t material to investors.

The rule would also have an impact on non-public companies. For example, a small entity contracting with a publicly traded company may have had to account for its greenhouse gas emissions to be included in the public company’s disclosures. The costs of the disclosures would have been passed down to consumers.

Shifting outlook

Chairman Uyeda, along with Commissioner Hester Peirce, voted against the rule. Each argued in the March hearing that the SEC was exceeding its authority and requiring disclosures that weren’t beneficial to investors.

Uyeda called the rule “climate regulation promulgated under the commission seal.”

“Today's rule is the culmination of efforts by various interests to hijack and use the federal securities laws like climate related goals,” Uyeda said.

Peirce argued the rule would “spam” investors with information that would "overwhelm" them.

“Congress did not create this agency to satisfy the wants of every investor, but to serve the interests of the objectively reasonable investor seeking a return on her capital,” Peirce argued. She also argued that only an act of Congress should direct the SEC to disclose information that’s “not clearly related to financial returns.”

In announcing his intention to move against the rule, Uyeda said the briefs the commission filed under former Chair Gary Gensler did not reflect his views. He said the lack of statutory authority was a key factor in his opinion, and he questioned if the agency, in adopting the rule, properly followed the Administrative Procedure Act.

In addition to his position on the issue, Uyeda said the changes in the composition of the SEC and President Donald Trump’s regulatory-freeze order led him to direct SEC staff to request the court not schedule arguments in the case against the rule. This will, he explained, provide time for the commission to deliberate on its position in the litigation.

Free market disclosures

Wake said that there’s nothing wrong with companies that maintain climate goals and disclose targets and progress, assuming their disclosures are accurate. The SEC disclosure rule, however, was problematic.

The PLF takes “issue with government agencies forcing companies to make disclosures that it has no business requiring them to make. It’s a free market. Companies can say what they like as long as they're not misleading consumers. And that's always been the case,” Wake said.

Wake said he hopes the new commission goes further than determining that the rule was unnecessary, but also that approving it had exceeded the agency’s authority.