Stats say mass killings at 20-year low, but Americans don’t feel it

In an information age when crimes can be — and are — broadcast in real time, Americans are confronted with violence every day, leading to skewed views on its prevalence. In reality, mass killings are close to a 20-year low.

Analysis of the recently-released Associated Press/USA TODAY/Northeastern University Mass Killing Database shows that 2025 is on pace for the lowest number of mass killings in more than 20 years.

"It's not rocket science. You make it risky for criminals to go and commit crime. Kash Patel has moved FBI agents out of the DC offices to around the country where the crime is. He's increased arrests by like 100% there. You know, make it risky for criminals to commit crime. They're going to commit less crime," that, according to economist and expert on guns and crime, John Lott.

The tally has dropped roughly 24% from 2024 and is down nearly 60% from the record 41 incidents in 2019. Criminologist James Alan Fox, who maintains the database, described the decline during an interview as largely a return to pre-pandemic levels after an unusual spike.

Mass murder, as defined by the Department of Justice, is the killing of three or more people at one time and in one location. The perpetrator is not counted among the victims.

Media attention: If it bleeds, it leads

Fox noted that sharp increases in mass killings typically receive heavy media attention, yet the recent steep decline has gone largely unreported outside of a few opinion pieces. He attributes much of the public’s heightened fear to round-the-clock television coverage and live video on both the internet and social media that did not exist during major incidents of the 1980s and 1990s. Without graphic, real-time footage, those earlier events faded quickly from national memory despite comparable death tolls.

One such example that left many Americans shaken was the public assassination of conservative advocate and founder of Turning Point USA, Charlie Kirk, in September. The video of the shooting quickly spread across social media within minutes of occurring.

While mass killings in private homes and gang-related incidents account for most cases, public attacks drive widespread anxiety because they appear random and unpreventable. Fox said improved firearm storage and closing background-check loopholes could reduce some incidents, but constitutional protections make Australia-style bans impossible in the United States. He expressed hope that wider awareness of the downturn might ease public fears fueled primarily by intense media exposure to rare events.

Social media amplifies the occurrence of violent crime

The widespread perception that crime is surging, even in periods when official statistics show stable or declining rates, stems primarily from social media algorithms that relentlessly amplify violent incidents, viral dashcam footage, and neighborhood-watch posts, creating the illusion of constant danger in users’ feeds.

Platforms like TikTok, X, and Facebook prioritize emotionally charged content — ring-doorbell thefts, subway attacks, or flash-mob robberies — because outrage and fear drive engagement, flooding timelines with decontextualized clips that feel immediate and local even when the events occurred months ago or thousands of miles away.

As a result, people overestimate both the frequency and proximity of crime, confusing what social media curates for them through digital exposure for real-world risk, fueling a feedback loop where anxious users unwittingly demand more “crime wave” content, further distorting public perception beyond what police reports or victimization surveys actually reflect.

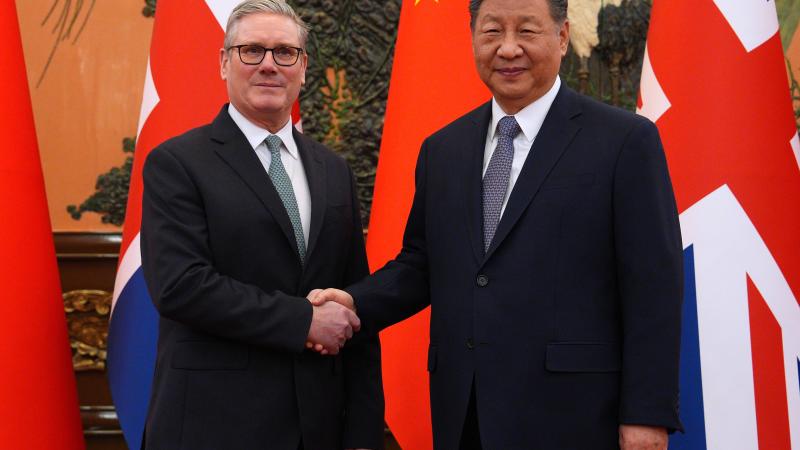

The decrease in mass killings could be attributed to some degree to the current work of the Federal Bureau of Investigation and its director, Kash Patel, who says the agency recently thwarted a possible terror attack in Michigan in October.