SCOTUS parrots gender ideology again, despite suggesting bans on males in girls' sports are valid

High court already adopted language and assumptions of transgender activists when it upheld Tennessee's ban on so-called gender affirming care for youth. Alito celebrated for perceived death blow to argument against Idaho's law.

When the Supreme Court upheld Tennessee's ban on puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones and surgery as treatment options for gender-confused youth last year, it unexpectedly riled up the law's supporters by adopting much of the language and assumptions of the gender ideology movement, including that sex itself can be changed.

It was deja vu all over again at the high court Tuesday for a pair of hearings on Idaho and West Virginia laws that ban males from competing in girls' sports, with apparently at least five votes for upholding the laws but the same activist lingo and pseudoscience.

Both Democratic and Republican nominees on the nine-member court described males who identify as the opposite sex as transgender "girls," "women" or simply "athletes" who compete against females, erasing the immutable maleness at the heart of the laws.

They barely acknowledged the thoroughly studied sex differences between males and females relevant to athletic competition, documented in friend-of-the-court briefs by sports physiologists, letting lawyer Kathleen Hartnett insist Idaho's stated purpose for the law did not exclude her male client, Lindsay Hecox, from women's competition.

Hartnett is trying to walk a tightrope, arguing that Idaho's rationale of protecting females from males' athletic advantage doesn't apply to males like Hecox who suppress their testosterone, which Hartnett claims erases male athletic advantage. That would make Idaho's law unconstitutional "as applied" to such males.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett came in for particular disdain on X for not only repeatedly using "trans girls" for males, and the activist term "cisgender" for people who identify with their sex, but also for claiming relevant sex differences don't materialize before puberty.

Idaho counsel Alan Hurst corrected Barrett on her question about how Idaho's argument would fare "if we're talking about six-year-olds," saying males still have "about a 5% athletic advantage over girls in most situations."

"Contrary to what Justice Barrett has stated, puberty suppression does not eliminate the male advantage in sports. Significant sex differences in athletic performance exist before puberty," evolutionary biologist Colin Wright wrote, citing exercise scientist Gregory Brown's essay for Wright's newsletter.

Science journalist Benjamin Ryan cited peer-reviewed papers by physiologist Michael Joyner and developmental biologist Emma Hilton in response to an NPR segment ahead of arguments that claimed research shows no inherent male advantage in sports and that Idaho and West Virginia banned "girls" from "playing sports."

Males still have an edge in women's sports even with "sustained testosterone suppression and estrogen treatment," and Joyner's research shows a "small but significant competitive advantage over girls" for boys before puberty, probably because of prenatal testosterone and "mini puberty" during infancy, Ryan wrote.

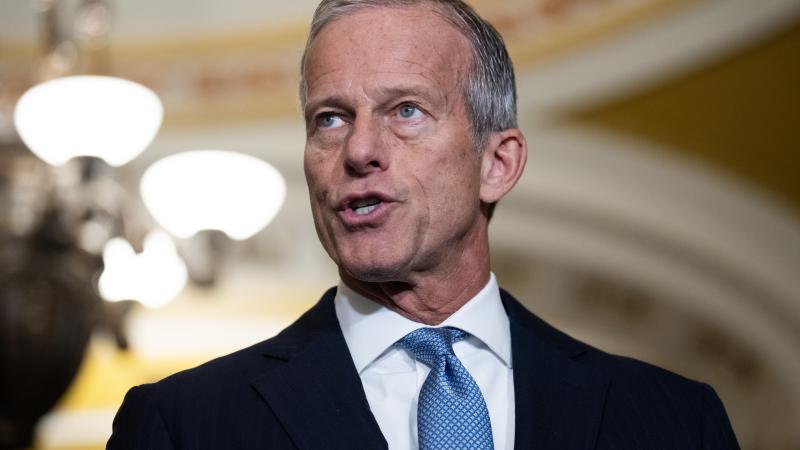

Justice Samuel Alito emerged as the conservative hero among the court's six GOP nominees through questioning perceived as the nail in the coffin to the Idaho challenge.

Hecox lawyer Hartnett agreed with Alito that schools can legally maintain sex-segregated teams, and that an equal protection challenge would require "an understanding of what it means to be a boy or a girl or a man or a woman," but Hartnett couldn't define "boy" or "girl."

"How can a court determine whether there's discrimination on the basis of sex without knowing what sex means for equal protection purposes?" Alito responded.

Hartnett also admitted it was permissible for a school to reject a male from the girls' track team, who identifies as a girl but had received no blockers, hormones or so-called gender-affirming surgery. When Alito asked whether such a person was a "woman," Hartnett answered she would "respect their self-identity in addressing the person."

Alito marveled that Hecox's lawyer had seemed to concede that discrimination on the basis of transgender status is legal.

Appeals court rewrote legislative history to make Idaho look bad

The Idaho challenge by Hecox, who is seeking to graduate from Boise State University this calendar year, came to the high court under peculiar circumstances, and justices probed Tuesday whether they could dismiss it as moot.

Hecox tried to dismiss the case after SCOTUS agreed to hear it, claiming the athlete had permanently stopped playing women's sports and ongoing litigation was threatening Hecox's mental health, safety and graduation prospects. The district court refused, calling Hecox's about-face "somewhat manipulative to avoid Supreme Court review."

Justice Sonia Sotomayor twice questioned why justices should force Hecox to continue, with Idaho counsel Hurst reminding her that unlike the court's Acheson Hotels precedent, Hecox's stated plans for women's sports have often changed over years of litigation.

Having a precedent named after you makes "your infamy live forever," Sotomayor said, asking Hurst whether he had studied the "notoriety" that follows plaintiffs. False, Hurst said: Hecox cited enduring negative attention "since the beginning" of the case, and there's "no background principle of 'plaintiffs get to leave the litigation whenever they want.'"

The West Virginia challenge presents similar issues but involves a high school athlete, Becky Pepper-Jackson, who has lived as a girl since childhood and started puberty blockers "at the onset" of male puberty.

Hurst told justices a West Virginia ruling won't necessarily apply to Idaho because the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals changed the definition of sex "for constitutional purposes" in its Idaho ruling, a question not reached by the 4th Circuit in B.P.J.

He corrected Sotomayor's claim that the legislative history explicitly referred to banning "transgender women," when the 9th Circuit inserted the phrase in brackets.

"Gender identity does not matter in sports" and the purpose of Idaho's law is "preserving women's equal opportunity," treating the sexes equally and "consciously choosing not to" judge based on gender identity, he said.

Competitive disadvantage for males on testosterone suppression?

Justices grappled with an existential question in constitutional law – whether there's such a thing as an "as-applied equal-protection challenge," as the Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review claimed two years ago – to decide how to treat Hecox's request for relief for males on testosterone suppression to compete in women's sports.

Principal Deputy Solicitor General Hashim Mooppan declared the case "the world's easiest as-applied claim to reject" because the "subclass" alleging discrimination is "a fraction of a percent," far lower than SCOTUS precedents that "rejected claims by people who had a much greater percentage than a fraction of percent."

Hartnett said Hecox was willing to undergo ongoing bloodwork testing to prove the athlete's circulating testosterone was comparable to that of females, and Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson said such testing was permissible. But Idaho's law also required an unconstitutionally invasive pelvic exam and chromosome test, Hartnett said.

Males in Hecox's situation actually may have a competitive disadvantage compared to females because the suppressed testosterone is mismatched with their male physiology, Hartnett said.

Hurst's rebuttal cited a submission by the United Nations special rapporteur for violence against women and girls, which documented more than 600 female athletes who lost nearly 900 medals to males identifying as women in more than two dozen sports. Idaho's law is not required to be a "perfect fit" for every instance of males competing as women, Hurst told the justices.

Justices John Roberts and Neil Gorsuch worried Hecox's argument would replace the intermediate or heightened scrutiny generally applied to sex-based claims, which only requires an "important government interest" accomplished by means "substantially related to that interest," with "strict scrutiny," which is much harder for governments to meet.

If SCOTUS allows a challenge by such a tiny subclass within all males identifying and competing as women, as Hecox proposes, that would seem to erase all distinctions by sex beyond athletics, Roberts said.

Gorsuch asked what portion of the evidence must favor Idaho on how puberty blockers and testosterone suppression affect male athletic advantage – 50-50, "70-20" or another ratio – for the state's law to be upheld. He cited the "healthy scientific dispute about the efficacy of some of these treatments" as relevant to deciding intermediate versus strict scrutiny.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh questioned why SCOTUS should "constitutionalize this" for the whole country given the scientific uncertainty and the close balance of states that allow versus ban males in women's sports.

Under intermediate scrutiny and SCOTUS case law, Idaho must only draw "reasonable inferences from substantial evidence" to justify excluding males from girls' sports, Hurst said. "It does not need to act only on scientific consensus." He assured the justices that Idaho wasn't trying to force its view on other states, just protect its own judgments.

The Facts Inside Our Reporter's Notebook

Links

- Supreme Court upheld Tennessee's ban

- adopting much of the language and assumptions

- hearings on Idaho

- West Virginia laws

- apparently at least five votes for upholding

- briefs by sports physiologists

- Kathleen Hartnett

- repeatedly using "trans girls"

- "cisgender

- sex differences don't materialize before puberty

- evolutionary biologist Colin Wright

- Gregory Brown's essay for Wright's newsletter

- Science journalist Benjamin Ryan

- Michael Joyner

- Emma Hilton

- NPR segment

- district court refused

- Acheson Hotels precedent

- Becky Pepper-Jackson

- Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review

- submission by the United Nations special rapporteur

- intermediate or heightened scrutiny

- "strict scrutiny,"

- SCOTUS case law