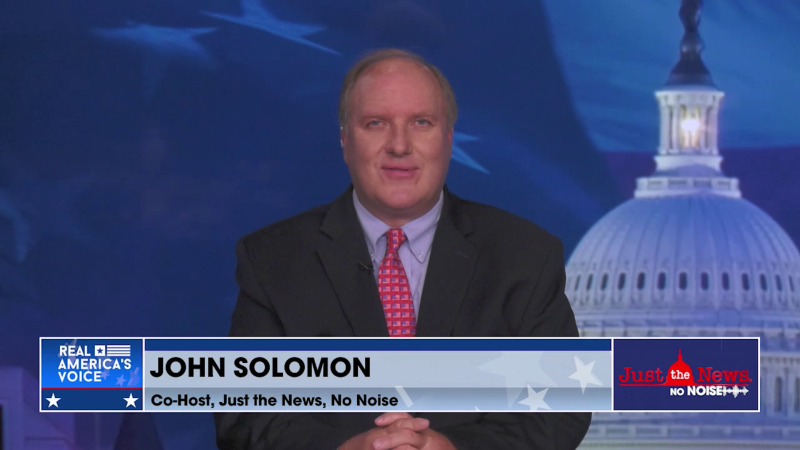

Restrictions on Pentagon press corps part of American history, despite uproar

The U.S. Wartime Censorship Office restricted content flows abroad and the War Department regularly censored journalist’s articles with sensitive material—neither of which the modern Pentagon has proposed.

Much of the Pentagon press corps has condemned new policies instituted by Secretary of War Pete Hegseth to curb the publishing of sensitive and classified information, but in fact, such restrictions are a longstanding American tradition, dating at least back to the Second World War.

Since taking the helm at the Pentagon, Hegseth has implemented several rounds of new restrictions on the press corps reporting on the military, including banning reporters from entering certain areas without an escort, barring them from offices of senior military leaders, and informing reporters of the Pentagon's prerogative to protect sensitive information.

That last requirement, which the secretary officially ordered last month, drew condemnations from the Pentagon Press Association (PPA) and legacy media as an assault on their profession and the First Amendment.

The PPA said the new policies "appear designed to stifle a free press” because they would force reporters to sign off on policies they disagree with. The association worries it would expose its reporters to prosecution for "simply doing [their] jobs."

“The policy conveys an unprecedented message of intimidation to everyone within the DoD, warning against any unapproved interactions with the press and even suggesting it’s criminal to speak without express permission—which plainly, it is not,” PPA said in a statement.

Censorship of military information nothing new

However, restrictions on reporters covering the U.S. military and its activities to protect classified, or sensitive information have a storied history in the United States.

As far back as 1918, The Sedition Act extended the Espionage Act of 1917 to cover a broad range of offenses, notably publications and even expressions of opinion that cast the government or the war effort in a negative light. The text of that language made it a federal crime to "publish any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of government of the United States, or the Constitution of the United States, or the military or naval forces of the United States."

World War II saw the first codified effort expressly directed at journalists. The Pentagon—known then as the War Department—implemented extensive restrictions on war correspondents covering the U.S. military’s role in the global conflagration.

The restrictions took shape in the wake of Executive Order 8985 issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor in Dec. 1941, which established the Office of Censorship—tasked with doing what its name suggests, censoring all communications “by mail, cable, radio, or other means of transmission” between the United States and any foreign country.

The order formalized preliminary censorship procedures established by the War and Navy Departments following the outbreak of war in Europe in 1939, historical records show. The government’s goal was to prevent sensitive military information from falling into foreign hands while the United States was at war.

The War Department’s “Regulations for Correspondents Accompanying U.S. Army Forces in the Field,” published the following month in Jan. 1942, detailed the compact between the armed forces and journalists covering them.

In order to receive credentials from the military, the correspondents were required to sign an agreement and promised not to publish sensitive military information.

But, WWII-era regulations went even further. It required journalists to submit articles for a censorship review by an intelligence officer, who had the authority to delete portions of the article he deemed to violate the terms. The 1942 policy directs all reporters to submit their dispatches to the intelligence officer or his assistant for censorship prior to filing or mailing their stories.

The agreement, which reporters were required to sign before earning credentials, stated: “I will govern my movements and actions in accordance with the instructions of the War Department and the commanding officer of the Army unit to which I am accredited, which includes the submitting for the purposes of censorship all statements, written material, and all photography intended for publication or release either while with the Army or after my return, if the interviews, written matter, or photography are based on my observations made during the period or pertain to the places visited under this authority.”

PBS filmmaker Ken Burns noted that "More than 30 government agencies were involved in censorship, but newspaper managing editors were often stricter than the censors. President Roosevelt set up the Office of Censorship right after Pearl Harbor. The Office of War Information suppressed visual material that it feared would threaten domestic unity."

The policy outlines what kinds of information the military censors would be assessing when they reviewed a correspondent's article.

“In general, articles may be released for publication to the public provided— (1) They are accurate in statement and implication. (2) They do not supply military information to the enemy. (3) They will not injure the morale of our forces, the people at home, or our allies. (4) They will not embarrass the United States, its allies, or neutral countries,” the policy reads.

You can read the historical regulations for war correspondents below:

Pentagon: "Only change is an update to our credentialing process"

“Despite many statements to the contrary, journalists are not required to clear stories with us, they retain robust access to our public affairs offices, the briefing room, and the ability to ask questions, which we continue to answer thoroughly. They can also move freely throughout the building. In sensitive areas where they can’t, they’ll simply need an escort,” Pentagon Press Secretary Sean Parnell said in a post to X last week explaining the new policy.

“The only change is an overdue update to our credentialing process, which hasn’t been revised in years—if not decades—to align with modern security standards. Such procedures are standard at military establishments worldwide, and the Pentagon is no exception,” he continued.

The primary purpose of the new regulations, Parnell said, was to protect against the unauthorized disclosure of classified or sensitive military information and to prevent journalists from soliciting such a disclosure from officials—a criminal act.

“Congress has made clear that unauthorized release of sensitive information by DOW personnel is a crime. Our policy is also clear: Soliciting DOW service members and civilians to commit crimes is strictly prohibited,” said Parnell.

After the backlash, the Pentagon released a revised version of the policy last week that, according to The New York Times, now says there is no prohibition on “constitutionally protected journalistic activities, such as investigating, reporting or publishing stories.”

For his part, Secretary of War Hegseth has remained firm on the concept, reportedly telling Fox News that "The Pentagon press corps can squeal all they want, we’re taking these things seriously. They can report, they just need to make sure they’re following rules."