Carbon tax goes before skeptical high court in Pennsylvania

Supreme Court justices struggled with the assertion, wondering aloud how far federal air regulation would let states go – could emissions from cars and cows come under scrutiny next?

(The Center Square) -

A skeptical high court grilled state officials this week about whether the money it wants to collect from a regional anti-pollution pact constitutes a fee or a tax.

Only the latter needs legislative approval, which will not happen with a split General Assembly, where the risk of rising utility bills 30% during economic uncertainty weighs heavily.

That means it’s up to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court to decide if the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative’s effort to limit harmful emissions from power plants across the mid-Atlantic rises above the financial impact residents may feel.

The Department of Environmental Protection believes it does, citing an interpretation of the federal Clean Air Act as proof. Joining the program, RGGI as it's called for short, could generate upward of $1 billion in revenue that would be split between administration costs, energy efficiency projects, and renewable resource investment.

Crucially, the money wouldn’t funnel into the state’s main bank account, unlike a tax, said Jennifer O’Neill, an attorney representing the Sierra Club and other environmental intervenors. She and Eric Hazlett, on behalf of the department, say the state has the authority to enter RGGI via regulation, making it the only state among 11 others to do so.

Supreme Court justices struggled with the assertion, wondering aloud how far federal air regulation would let states go – could emissions from cars and cows come under scrutiny next?

“Maybe they are looking at every individual family's automobile going down the road blowing out CO2 carbon emissions and maybe they thought well that’s where we want to look now,” said Justice Sallie Updike Mundy. “And I ask you for input whether this could be used to create a market for every family in Pennsylvania to have to go through a RGGI auction to buy carbon emissions so that they can take their kids to school and go grocery shopping?”

The goal of RGGI is to lower greenhouse gas emissions, reduce climate impacts, and incentivize a transition to renewable energy.

On the East Coast, a pool of generators from 11 states buy “credits” that cap how many tons of carbon dioxide they can release into the atmosphere. Producers that exceed their cap can buy credits from others in the pool, but the total amount available will decline each year until zeroing out in 2040.

That auction is called RGGI, and since 2009, its credits have collectively reduced greenhouse gas emissions 50% faster than the rest of the country and returned $6 billion back to its member states.

In Gov. Josh Shapiro’s first budget proposal, he counted on more than $600 million in revenue from the program to support investments in public assistance programs, tax credits, career incentives, and public education.

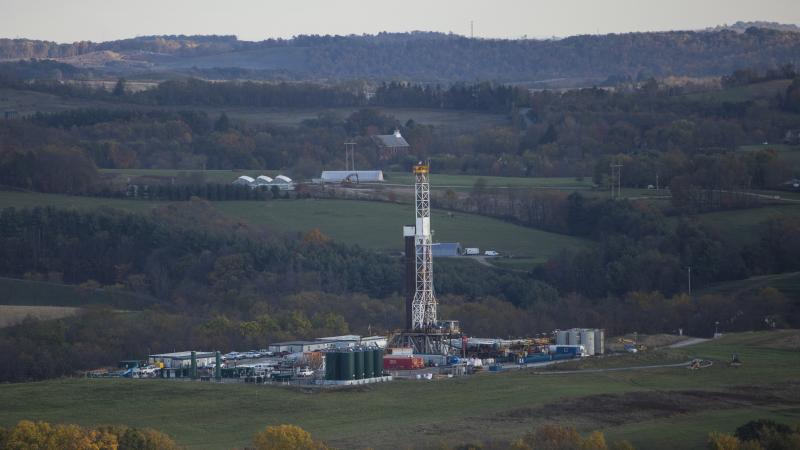

Many agree that Pennsylvania’s participation would be nothing short of a seismic shift. As the nation’s second-largest natural gas producer and leading energy exporter, embracing regulations meant to accelerate the transition away from fossil fuels alarms an unlikely coalition – natural gas developers, legislative Republicans, and labor unions – about the economic impact of carbon “taxing.”

But it’s also a prime target for reducing Pennsylvania’s carbon footprint and tackling climate change. The Department of Environmental Protection says modeling shows joining RGGI will slash carbon dioxide emissions as much as 225 million tons by 2030.

When Commonwealth Court struck down Pennsylvania’s entry into the program as an unconstitutional tax in November, Shapiro appealed. In the meantime, he introduced his own Pennsylvania-specific version of the program and urged lawmakers to pass it instead.

Whether within state borders or beyond, critics of RGGI said it still has the same problems: costing thousands of jobs by trying to regulate air that drifts freely and is uncontained by the program’s borders.

“We are talking about loss of jobs, which by the way has already occurred because of the uncertainty of the regulation … the shuttering of large parts of the whole industry,” said David Fine, an attorney representing power generators impacted by the program. “If that’s to happen, that should be a decision, a policy decision made by the General Assembly, not by the EQB and the DEP, but that’s not what happened here. This is unconstitutional.”

EQB is an acronym for the Environmental Quality Board.