How Nevada became key proving ground for Democrats' national mail-in ballot push

Dems make safety the issue. 'You shouldn't have to put your life at risk in order to exercise your constitutional right to vote,' Nevada Assembly Speaker Jason Frierson says.

With the 2020 General Election getting ever closer, America is about to embark on a challenging journey never before seen in this country: widespread universal mail-in balloting in the age of COVID-19.

Rather than just simply showing up at the polls this year, voters in nine states and the District of Columbia will actually receive ballots in the mail, making this the most robust, and potentially problematic vote-by-mail effort ever in our nation’s history.

Proponents of the controversial practice say providing this new stricture is a matter of life and death.

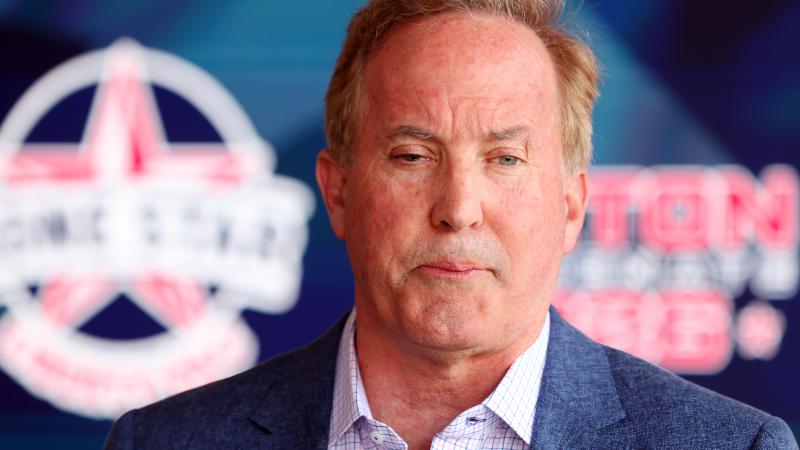

“You shouldn't have to put your life at risk in order to exercise your constitutional right to vote,” Nevada Assembly Speaker Jason Frierson says. “We're at an unusual time with the national pandemic and I think that we needed to make sure that folks who are eligible are able to vote safe.”

Frierson authored a controversial bill, now a law in Nevada, that guarantees every active registered voter will get a ballot in the mail because a statewide disaster or emergency declaration has been issued.

President Trump called the bill a, “disgrace," and the Trump administration is suing, arguing that it “upends Nevada’s election laws and requires massive changes in election procedures and processes, makes voter fraud and other ineligible voting inevitable.”

The legal action also highlights language in the bill that they believe unconstitutionally extends the deadline for Election Day. A provision makes it allowable for ballots with unclear postmark dates to be accepted up to three days after Election Day.

Frierson says this is all much to do about nothing. “We will have a process in place where we will count the ballots that were cast on or before Election Day," he tells Just The News. “If there's a discrepancy afterwards, we're letting our local election officials adjust and make sure that they are addressing that discrepancy but only for ballots that were cast on or before Election Day.”

Of course that begs the question: who are these local officials who will be entrusted with deciding what ballots are valid and which ones are not. “I think that we are creating a problem that doesn't exist,” Frierson says. “We are not in the Florida, ‘hanging chad’ era here.”

Part of the other problem in the law, according to conservative critics, is the issue of ballot harvesting, in which a third party is allowed to deliver or submit a ballot on another’s behalf. It’s legal in California and now it’s lawful in Nevada as well.

At the national level, since the coronavirus pandemic began, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and congressional Democrats have been trying to push through funding for ballot harvesting but it hasn’t gone anywhere.

Still, Frierson, who was able to get it passed in Nevada, sees nothing wrong with it. “I think it's a cry to mischaracterize what it is,” he says. “It's simply assistance. It’s assisting somebody making sure it gets delivered.”

With six electoral votes up for grabs, Nevada will be a key state in 2020. Hillary Clinton barely beat Donald Trump here in 2016: just two percentage points separated them.

Every vote will be critical, and that’s why Democrats like Frierson are looking to give certain voters a boost. He says there are people that don't have transportation, access to the Internet or the means to get to the polls in person, not to mention those who won’t want to wait in anticipated long lines.

“There are people that are not going to be willing to wait in line for hours, which is why we were motivated to make a change and expand access to the polls.” But if people are willing to wait in line at places like Walmart, why should a voting station be different? “I missed the part of the constitution that says you have the constitutional right to go to Walmart,” Frierson says. “We're talking about a constitutional right here.”

Mailing voters ballots has some serious fraud issues attached to it. A Pew Research Center study shows roughly 24 million voter registrations are no longer valid.

“Now you've got tens of millions of ballots that are not going to actual voters, which is going to create tens of millions of ballots and create opportunities for fraud,” says Eric Eggers, author of the book, “Fraud: How the Left Plans to Steal the Next Election."

Compounding the problem is the fact that universal mail-in balloting is much different than absentee balloting, a system that has been in place for decades with a higher threshold of checks and balances.

“There’s a difference between requesting and using an absentee ballot in the manner in which our current democratic systems are set up,” Eggers says. “Mailing everyone, whether they requested a ballot or not is a very different scenario.”