Climate superfunds in N.Y., Vermont will harm consumers even if courts nix them, experts say

Vermont and New York passed “climate superfund” laws, which levy billions in fines against oil companies for legal products, and now other progressive blue states are considering them. The laws face legal challenges, but however courts decide, consumers will pay the costs, experts say.

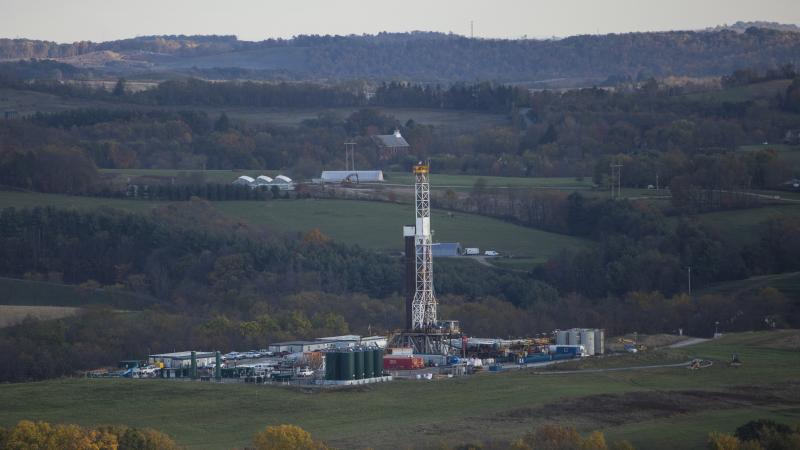

Last year, Vermont and New York passed “climate superfund” laws, which have levied billions in fines against oil companies for producing legal products over the past few decades. The money extracted from these companies would then go to ameliorate what supporters of these laws say are the damages caused by climate change. Their solution includes billions of dollars in infrastructure projects, disaster relief and renewable energy projects, among other things.

Lawmakers in several other blue states are considering such legislation. Critics of these laws say that they’re going to drive up energy costs and discourage much-needed investment in energy infrastructure. And that’s true, they say, whether the laws withstand legal challenges or not.

“We see anti-energy activists who, increasingly frustrated with the progress being made in Washington, have sort of turned to state houses and the courts to advance their agenda,” Tom Pyle, president of the American Energy Alliance, said during a webinar Tuesday on the superfund laws, hosted by the Institute for Energy Research and C3 Solutions.

Energy liability regimes

The Department of Justice filed lawsuits in May against New York and Vermont challenging these laws, and a coalition of states have also filed their own lawsuits against the laws.

Filings in the suits use similar language to argue that the states are trying to seize control of the nation’s energy industry, and the money these laws are extracting from companies would ultimately be paid by consumers. The energy industry is managed by a framework of different state and federal entities, each with their own specified jurisdiction. Opponents of these laws say that the progressive states are wresting away what should be the domain of the federal government under Article 1, Section 8, Clause 3 of the U.S. Constitution. Known as "The Commerce Clause," it has historically been viewed as both a grant of congressional authority and as a restriction on the regulatory authority of the States, particularly on interstate commerce.

Pyle said, besides increasing costs of energy, which impacts all businesses, the laws could create a patchwork of “energy liability regimes,” undermining U.S. energy security.

“They don't pay for these things. We do. We pay for it in the form of higher gas prices, higher energy prices,” Pyle said.

Carbon tax by another name

Ian Banks, research fellow for C3 Solutions, explained that the term “superfunds” have historically referred to specific, discrete polluted sites. The costs of cleaning up those sites are borne by the parties responsible for creating those sites.

Climate change, on the other hand, he explained, has no specific, discrete site. It’s a global phenomenon. We all emit greenhouse gases in the course of our daily lives, and attributing those emissions to extreme weather events is full of uncertainty. So, trying to assess the responsibility for climate change, Banks said, is a very difficult process.

“One state, attempting to take action to mitigate or remediate the effects of climate change on their state by exacting fees and costs onto companies, in many ways, is just a carbon tax by another name,” he said.

Donald Kochan, professor of law and executive director of the Law and Economics Center at George Mason University, explained that with traditional superfund laws, the Environmental Protection Agency holds a potentially responsible party responsible for the remediation and damages from a polluted site. There can be multiple parties involved, but they can all share responsibility for the cleanup. That direct responsibility doesn’t exist with climate superfund laws.

“I believe that largely these labels were done for convenience's sake, to try and legitimize the legislation and to try and make it sound like it wasn't such a deviation from norms to do this kind of thing,” Kochran said.

Retroactive liability

He said for the past 15 years or so, there’s been a concentrated effort to find different legal avenues to hold energy companies liable for climate change. There've been various iterations of this effort that have failed, and activists are trying different strategies to figure out what will work.

“So these are state-based legislative laws, they are largely coming as part of an overall … climate warfare lawfare, or you might call it the climate liability ecosystem,” Kochran said.

Kochan explained that the retroactive liability that climate superfund laws place on companies creates uncertainty for all industries, which will be very disruptive to the overall market.

“People can't depend on a rule of law which makes investment go down overall. This has effects on the overall economy for all kinds of industries and all kinds of products. If this can happen to the energy industry, it can happen to anyone, in which we just say that retroactively, some lawful product can now be deemed as subject to a fine. That means that people just don't have confidence in some of their investments and the possibility of return on investments they're making today, because I don't know what my liability is going to be tomorrow. ” Kochan said.

Jessica Weinkle, associate professor at University of North Carolina-Wilmington, said the climate superfund laws are seeking damages to address disaster losses. Sometimes this is in areas where the infrastructure has aged and is in dire need of repair.

“So there's this pursuit of litigation to provide the funds to address what is ultimately a rather significant infrastructure issue and policy issue, which has not really been dealt with over the years,” Weinkle said. So climate superfund laws are ultimately shifting responsibility from policymakers to oil companies.

Professionalized scientific discipline

The thread of science being developed to attribute extreme weather events to greenhouse gas emissions, specifically in service to climate litigation, is also problematic, Weinkle said.

“It's sort of celebrated within certain colleges. And so you're seeing a professionalization of this practice. And the merits of that practice are debated significantly and are highly controversial. I think there are serious ethical concerns about it, given that the whole methodological pursuit was born by the want to pursue litigation,” Weinkle said.

How well that science will stand up in court is yet to be seen. The climate litigation cases winding their way through the courts, Kochan said, haven't gotten to the trial stage yet — none of them have.

“We've not yet gotten to where the plaintiffs actually have to prove traceability, causation and harm and effect,” he explained.

At that point, the motivations behind the scientific methodology should keep attribution science out of the court, Kochan said. “The judge has an obligation to act as a gatekeeper against the introduction of that kind of science. And that's why I think that there will be a very, very difficult road for all the plaintiffs in the climate change litigation to ever win,” he said.

In the legal challenges to climate superfund laws, however, the political motivations behind attribution science won’t matter as much, Kochan said.

“The legislature, pretty much, is free to accept the worst kinds of arguments in favor of legislation. The courts won't be looking past that to say, ‘Oh, this was a bad policy decision,’” he explained.

Public relations campaign

Weinkle pointed out that attribution science also serves as an advocacy campaign. The media often report on the studies coming out of climate advocacy groups like the World Weather Attribution (WWA), even though they’re not peer-reviewed, and there’s no mention in these articles that the group behind the research was formed to win lawsuits against oil companies, something of which its founders make no secret.

“It’s more or less constant messaging,” Weinkle said. Younger people are growing up in this environment where these messages are dropped on them incessantly, and Weinkle said getting people to see past what they’re hearing everywhere will be a challenge.

The Facts Inside Our Reporter's Notebook

Links

- Vermont

- New York

- several other blue states

- Institute for Energy Research

- C3 Solutions

- Department of Justice filed a lawsuit

- superfunds

- viewed

- concentrated effort to find different legal avenues

- various iterations of this effort that have failed

- attribute extreme weather events to greenhouse gas emissions

- World Weather Attribution

- something its founders make no secret of