Trump administration pursues boosting domestic rare earth supplies, China shows why they’re needed

Breaking the China chain: The Trump administration has been taking steps like reducing tariffs, trying to develop domestic supply chains in hopes of breaking China’s control of critical minerals. Experts say it will take years before the efforts bear fruit.

In response to the ongoing trade war with the U.S., China this month disrupted supply chains of vital critical and strategic minerals by slow-walking exports. With near-complete control of the markets for rare earth magnets, the move got the world’s attention.

The Trump administration has been taking steps to try to develop domestic supply chains in hopes of breaking China’s control of critical minerals, but it will take years — some experts say decades — before the efforts bear fruit. While the results are long-term, experts say the actions the federal government is taking will help break that chain.

Critical minerals are usually defined as essential for national or economic security, with vulnerable supply chains, and important for manufacturing essential products. Strategic minerals, on the other hand, are often considered essential for national defense and the overall strategic makeup of a country, and may or may not have vulnerable supply chains.

“This is an area I'm actually very pleased about. They're [the Trump administration] on fire to figure this out there. They're all hands on deck, trying to figure out what levers they have within government, what they don't, and what they need to bring in to give them the ability to help out this industry. And they understand very well the need — the full supply chain, from mining, the processing, the metal making, to magnets — that this needs to be supported,” Joshua Ballard, CEO of USA Rare Earth, told Just the News.

China strikes back

Rare earth magnets are used in everything from iPhones to medical equipment. They’re also used in several ways in modern automobiles. As China strained supplies of the magnets, automakers in Europe and the U.S. were in a “full panic,” Reuters reported Monday. The New Indian Express reported last week that India’s automakers were in just as much trouble. After flexing its trade muscles, China’s Ministry of Commerce Saturday, CNBC reported, said it was easing the restrictions for European and American carmakers.

Trade negotiations between the U.S. and China resumed this week, Bloomberg News reported, following a phone call between President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping last week. It’s uncertain whether the negotiations will result in an agreement and a restoration of critical mineral supply chains, but this wasn’t the first time that China weaponized its dominance of rare earths.

Energy author and journalist Robert Bryce documented nine times since 2010 that China restricted rare earths as leverage in various disputes. In 2019, the Trump administration announced new tariffs, and shortly after, China’s state-controlled media outlet, People’s Daily Online, ran a headline warning, “United States, don’t underestimate China’s ability to strike back.”

“As some American politicians continue threatening to exert extreme pressure against China, people are increasingly concerned about what trump cards China holds against such suppression,” the Chinese reporter wrote.

Last December, China banned the export of gallium, germanium and antimony in response to the Biden administration’s crackdown on China’s semiconductor industry. Besides being used in bullets, missiles, nuclear weapons, and night-vision goggles, these elements are also used in lead-acid batteries and as a flame retardant. Gallium is used in electronics and semiconductors, and germanium is used in fiber optics, solar cells, and light-emitting diodes (LED).

China has also been known to flood the market and depress commodity prices in order to shut out competition.

Washington takes action on supply chain problems

The need to develop domestic supply chains hasn’t escaped the Trump administration’s attention. In March, Trump signed an executive order aimed at creating domestic supply chains from a variety of sources. The order invokes the Defense Production Act, which grants the president a wide range of authorities to influence the domestic industrial base in the interest of national security. Among other things, the order also expedites federal permitting for mineral production projects, and it empowers agencies to use not-yet-allocated funds to facilitate domestic mineral production.

In April, the White House issued a list of mining projects targeted towards expedited permitting processes. Last week, Trump issued a waiver of statutory requirements, including some congressional funding approvals, “for supply chains associated with munitions, missiles and associated equipment, and critical minerals.” This was also carried out with authority granted to the president by the Defense Production Act.

Trump also announced in April he would exempt from tariffs the raw forms of a variety of metals, including rare earths, according to S&P Global. David Hammond, a mineral economist with decades of experience as a mining consultant, told Just the News that in his opinion, this was likely due to the Trump administration coming to terms with the way raw minerals are processed.

The U.S. has limited capacity to refine the raw ore that it does mine. As a result, U.S. companies have to sell the raw ore to countries like China and Japan that have the capacity to refine it.

"We don't send them there for them to process and give us back the refined copper. That's not how the market works," Hammond said. Instead, we sell them the raw ore. They refine it, and then they sell us back the refined material. This means there are tariffs on exporting the material and tariffs on importing the refined products back into the U.S. "The lightbulb about that type of processing may have finally gone on in Washington," Hammond said.

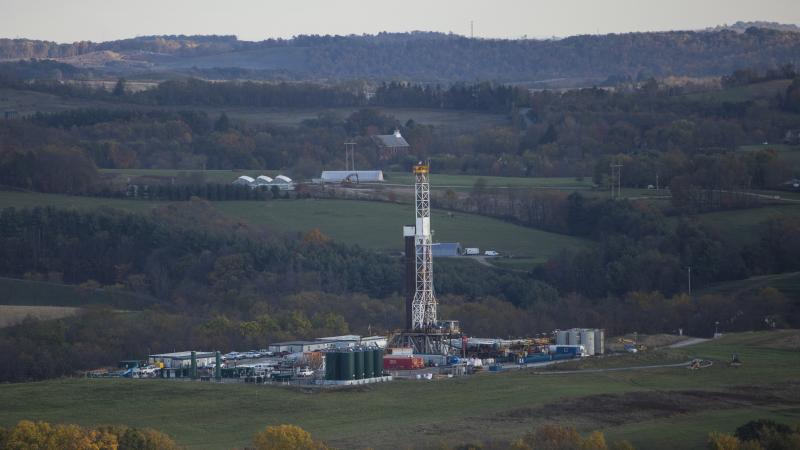

Developing domestic supply chains

USA Rare Earth built a large lab in Stillwater, Oklahoma, where the company is based. There, they have been developing prototype magnets for the company’s customers. The prototypes, Ballard, their CEO, explained, allow the customers to measure the quality of the magnets, make sure they’re meeting specifications, and ensure USA Rare Earth can satisfy their needs. Ballard said the company expects to go into full production next year.

The magnets are about 70% iron and about 30% neodymium and praseodymium, plus some other metals. The majority of materials in the magnets, Ballard said, is sourceable outside of China. He said he’s pretty confident that sources of neodymium and praseodymium can be developed outside of China as well.

Where it gets hard is in heavy rare earths, such as dysprosium, Ballard said. USA Rare Earths has a deposit in West Texas that’s very rich in heavy rare earths, and Ballard said they expect to develop those in the next few years. Processing of the ore is another hurdle, and currently, China controls 90% of the rare earth processing.

“As of today, almost all rare earths are at least processed by China,” Ballard said.

Important moment

Regardless of what happens in the trade negotiations with China, Ballard said it won’t change the fact that U.S. companies need to diversify their supply chains.

“Whether or not there's a loosening in China's policy, it doesn't change the fact that industries have opened their eyes to the fact that they need to diversify and that there's a real critical path here that they need to address. So I think that's a really important moment as we think about how this develops,” Ballard said.

However, that’s not something that’s going to be done overnight, and China is way ahead of the U.S. in this market. Since the 1990s, China has invested billions of dollars in rare earth mining and refining. They’ve also developed these industries without the environmental standards that the U.S. has. While that has given them a competitive edge over Western nations, it’s also caused serious environmental consequences.

U.S. lags behind Zambia in developing mines

The U.S. may have gone too far with its environmental standards. An S&P Global study last year examined 268 average development times from discovery to production across the globe and determined that on average, new mines in the U.S. take 29 years to begin production. Only Zambia had mines that took longer. This is largely due to the gauntlet of lengthy permitting and environmental litigation that all mines in the U.S., and much of the Western world, must go through.

Hammond said that he and other mineral economists have been in discussions with the Department of Energy leadership, trying to explain the challenges to mining that create these decades-long periods to bring a mine to production. He thinks the Trump administration may be coming to realize that its goal of domestic supply chains flowing from new mines is a goal that will outlive this administration.

Should USA Rare Earth go into production at its magnet facility in Stillwater within a year as planned, Ballard said the company should produce about 1,200 tons during 2026. That’s approximately 2.5% of the U.S. market. At their expected peak of production, which he said would take a few years, they’ll get to 5,000 tons per year, or about 10% of the U.S. market.

“It's going to take a few years, but we'll get there. I think it's an exciting time for the rare earth industry. That's for sure,” Ballard said.

The Facts Inside Our Reporter's Notebook

Links

- USA Rare Earth

- Reuters reported Monday

- New Indian Express reported last week

- CNBC reported

- Bloomberg reported

- Robert Bryce documented nine times

- United States, donât underestimate Chinaâs ability to strike back

- China banned the export of gallium

- flood the market and depress commodity prices

- executive order

- Defense Production Act

- White House issued a list of mining projects

- issued a waiver of statutory requirements

- according to S&P Global

- controls 90% of the rare earth processing

- serious environmental consequences

- S&P Global study last year